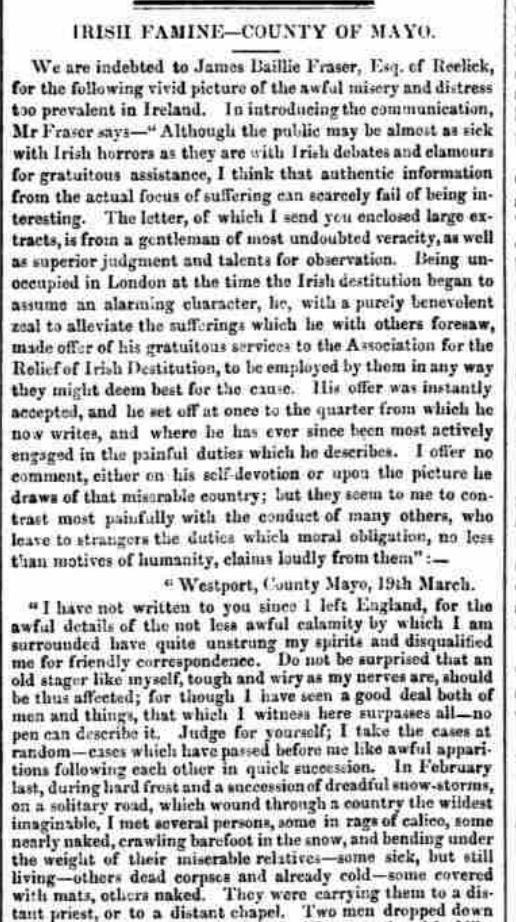

Felix Molski, a Kosciuszko Heritage (KH) committee member, and Ernestyna Skurjat-Kozek, the president of KH, have unearthed a previously unknown letter by Sir Paul Edmund Strzelecki.

The letter was published in the Inverness Courier on March 31, 1847.

In it, Strzelecki details the distress that he observed in Ireland during the Great Irish Famine.

“There is absolutely no doubt that the author of the letter is Paul Edmund Strzelecki, even though he is not directly identified,” says Felix. “It is a most interesting letter”.

The letter first appeared in an article published on Puls Polonii.

A transcript of the letter can be found below.

We are indebted to James Bailey Fraser, Esquire of Reelick, for the following vivid picture of the awful misery and distress too prevalent in Ireland. In introducing the communication, Mr. Fraser says – “Although the public may be almost as sick with Irish horrors as they are with Irish debates and clamours for gratuitous assistance, I think that authentic information from the actual focus of suffering can scarcely fail of being interesting.

The letter, of which I send you enclosed large extracts, is from a gentleman of most undoubted veracity, as well as superior judgment and talents for observation. Being unoccupied in London at the time the Irish destitution began to assume an alarming character, he, with a purely benevolent zeal to alleviate the sufferings which he with others foresaw, made offer of his gratuitous services to the Association for the relief of Irish destitution, to be employed by them in any way they might deem best for the cause.

His offer was instantly accepted, and he set off at once to the quarter from which he now writes, and where he has ever since been most actively engaged in the painful duties which he describes. I offer no comment, either on his self-devotion or upon the picture he draws of that miserable country; but they seem to me to contrast most painfully with the conduct of many others, who leave to strangers the duties which moral obligation, no less than motives of humanity, claims loudly from them”.

Westport, County Mayo, 19th March

“I have not written to you since I left England, for the awful details of the not less awful calamity by which I am surrounded have quite unstrung my spirits and disqualified me for friendly correspondence. Do not be surprised that an old stager like myself, tough and wiry as my nerves are, should be thus affected; for though I have seen a good deal both of men and things, that which I witnessed here surpasses all — no pen can describe it. Judge for yourself; I take the cases at random — cases which have passed before me like awful apparitions following each other in quick succession.

In February last, during hard frost and a succession of dreadful snowstorms, on a solitary road, which wound through a country the wildest imaginable, I met several persons, some in rags of calico, some nearly naked, crawling barefoot in the snow, and bending under the weight of their miserable relatives — some sick, but still living — others dead corpses and already cold — some covered with mats, others naked. They were carrying them to a distant priest, or to a distant chapel. Two men dropped down before me, while speaking, and died — life was extinguished like the flame of a lighted candle.

And, now that sickness or discouragement has driven the greater number to their hovels, I find in these often a whole family lying naked on straw; some laboring under dysentery — some swelled and dropsical — some under typhus fever — but all cowering under the same ragged blanket, frequently without fire or any available food. Sometimes, in visiting these lonely receptacles, of destitution, I have been obliged to force the door open, and found the inmates all dead! In a word, the misery met with here is utter and absolute — naked as it were, and unmitigated — alike destitute of moral and physical consolation — hopeless beyond relief — the point where death and life seem blending together.

All the combined efforts of Government and the association, with the aid of private charity, are inadequate to arrest the progress or check the effects of this calamity; and this, I grieve to say, not so much from insufficient means, as from the inertness of the lower, and the apathy and demoralization of the upper classes, which deprive both Government and the association of that potent and effective aid which they had a right to expect in the struggle they have engaged in for that suffering country.

I have under my charge the most destitute part of Ireland — the Counties Galway Mayo, Sligo and Donegal, on the north-west coast. From the depots of provisions which I have established at Clifden, Westport, Sligo, Killibeggs, etc I was, as you may suppose, very anxious to relieve all this distress; but to do so is most difficult, as it is most difficult to find trustworthy persons for the administration of details in allocating and distributing food to distressed individuals or families.

Private interest and jobs shamefully defeated the Government relief, and threatened the same with that which the association sent to Ireland; and but for the energy and ability displayed by the South Sea House committee, of which Jones, Lloyd, Rothschild, C R Smith, Abel Smith, Raikes, Baring, etc. are active members, the liberal subscriptions of the English public in 1847 would have shared the lot of that in 1822.

The inertness of the poor peasantry may lay claim to indulgence and commiseration, because it proceeds from ignorance; superstition makes them fatalists, while long starvation, or inefficiency of food, paralyzes their energies and renders them torpid. They know not how to help themselves. Besides, they are victims of an educated and higher class, who know the better, but pursue the worse course — who, though they witness in England the beneficial and civilising influence of resident landlords, refuse to follow that important example. But retribution is at hand, though the innocent suffer with the guilty; for if famine and pestilence send the one to a coffinless grave, under the ground, the new poor law, and late parliamentary enactments in reference to the duties of landholders, will, I trust, sweep the others from the surface of it; for, observe, the brawling and noise of the rich demagogues about Catholics and repeal, serve only to drown the voice of truth and hide the real evil, the curse of Ireland, which is neither religious nor political.

It lies in this, that the majority of the landlords are bankrupts, while the most of those (the minority) who are not so are absentees; and in the fact that both, after having debased and demoralized the lower order, threw them ultimately as a burthen on the Imperial Government. But Government will hit them through the measure of outdoor relief; for those who have a real bona fide interest in the preservation of their property, will be forced to look, as they never did before, to the improvement of their tenantry; while those who are virtually insolvent must just give up their nominal right to the land, and give place to a better class — to capitalists who will better discharge a landlord’s duty. But this requires time, and I dread the protracted sufferings to which those who survive may be exposed, although a better provision to meet their wants will produce some alleviation.

It is difficult to prognosticate how many may be carried off by the disease which is now raging. I do believe —–‘s estimate will not be far from the truth. Here winter appears to have terminated and spring about to begin, and with it those infectious diseases consequent on famine and privation. Already dysentery and fever, of the typhoid type, is raging and carrying off many. I am prepared to face it as I did cholera, and I hope as successfully.—Adieu

![Count Paul Edward [sic.] Strzelecki (copyright: the State Library of Victoria)](https://www.kosciuszkoheritage.com/public_html/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/2014_06_20.jpg)