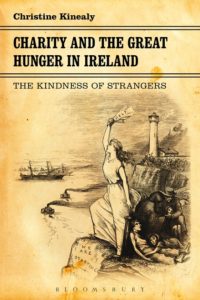

Felix Molski, one of the committee members of Kosciuszko Heritage, has written a review of Christine Kinealy’s new book Charity and the Great Hunger in Ireland: The Kindness of Strangers (published by Bloomsbury).

Kinealy – a Professor of History at the Caspersen Graduate School at Drew University in New Jersey – is a world-leading expert in the study of the Great Hunger.

Felix’s full review is published below.

Christine Kinealy’s new book, Charity and the Great Hunger in Ireland: The Kindness of Strangers, is a paradigm shift in an Gorta Mór literature. I believe it to be the most significant book yet published about the Great Hunger. No understanding of this period is complete without due consideration being given to the full gamut of human character: the bad and the ugly, but the good and heroic too.

As soon as people from all four corners of the world learned of the grievous circumstances of their ‘brothers and sisters’ in mid nineteenth century Ireland, the oft-latent good side of human nature was sparked; overwhelming generosity met overwhelming suffering and despair.

Christine Kinealy analyses the ‘intertwined’ threads of this fated relationship and, as we read, what we experience is like the development of a photograph in a darkroom. A detailed picture of the period begins to emerge in our minds. Two hundred and ninety one perceptive pages are supported by seventy seven pages of footnotes, nearly two thousand in all. Professor Kinealy has scoured all archives, libraries and sources to find every possible skerrick and morsel of documentation to give us added insight into the tragedy as it unfolded and the human response from across the globe in all its manifestations. Even a reference to a £5 donation made by a backwoods lawyer from Springfield Illinois was chased down. (That lawyer later became the 16th President of the United States!)

“Infinite variety” is how David Attenborough described and marvelled about animal and plant life in ‘Life on Earth’ and an ‘infinite variety’ of ‘The Kindness of Strangers’ can be discovered between the covers of Charity and the Great Hunger in Ireland. The cornucopia of benevolence therein can be cherry picked by anyone interested in doing further research or it can be used to find anecdotes of goodness for goodness sake. Each chapter begins with a meaningful quote beckoning the reader to enter; an appetiser creating an air of expectancy and anticipation of discovery; of learning.

The good works of the Society of Friends in Ireland and the USA is examined in detail. The indiscriminate benevolence of the Quakers in response to an Gorta Mór is well known. Nearly every book published about this tragedy to some extent mentions the help ‘Friends’ provided to the starving. Helen E. Hatton’s book The Largest Amount of Good in particular, also covers much of this ground. Professor Kinealy, however, brings into the spotlight all major responders to Irish need. For example, the endeavours of the British Relief Association, which, in fact, was the largest (and very successful) charitable organisation involved in providing relief to Ireland, is explored thoroughly.

The benevolence of the Association’s(BRA) chief agent, Paul Edmund Strzelecki, features prominently. The impact of the innovative scheme Strzelecki devised for clothing and feeding children through the medium of schools, as well as his hygiene requirements, is described and its positive results assessed. Christine Kinealy documents the huge impact of this simple idea with some of the typical observations made in the many written reports praising the scheme.

The magnificent charitable works of women such as the author Maria Edgeworth and Asenath Nicholson are also given the recognition they deserve, but so too are the thousands of women who anonymously provided a wide range of indispensable services to the needy. A chapter is dedicated to the vital role of the Catholic Church but Protestant benevolence and the benevolence of all major religions around the world is not neglected.

Poignant contrasts heighten our attention. For instance, strict, inflexible and heartless ‘official’ relief is compared to direct, efficient and empathetic ‘private’ relief. The contributions and impact of the elites of Britain and from around the world are juxtaposed with examples of those offering their ‘mite’ despite their own dearth. The gesture of the Choctaw Indians is well-known, but Professor Kinealy provides many other examples such as donations made by slaves, by ‘fallen women’, by low paid workers, and by schoolchildren.

Relief myths, controversies and motivations are scrutinised within the political issues and social attitudes framework of the period. Critics and naysayers – legitimate or not – always exist, but although the criticisms are discussed, Christine Kinealy keeps our focus on the ‘Good Samaritans’ who provided help with purity of soul. The point is made that it wasn’t the mean-spirited groups and individuals who ended the kindness of strangers; some of the attention was redirected to helping Irish immigrants. However, the unprecedented benevolence came to a premature end mainly because of the mistaken perception that the emergency had passed.

Charity and the Great Hunger in Ireland has soul. It is an essential companion to any other book about Ireland’s Great Hunger, and, because the author has provided a crisp, clear and concise context – the how, where and why of the Hunger – the book can stand on its own as well. It is a must-read for any serious student, because, for the first time, ‘man’s humanity to man’ during an Gorta Mór is comprehensively, authoritatively and definitively explored.

Felix Molski

This review has also been published in other media: